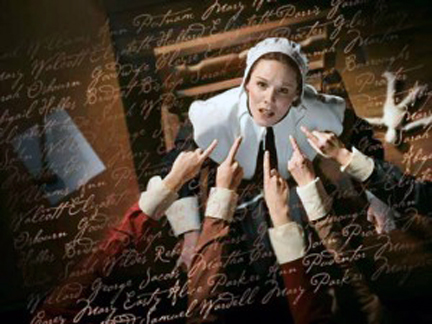

In 2011, I was substitute teaching in a high school English class. That day, the lesson plan for one class called for a section of Act 2 of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible to be read aloud. This is a fictionalized historical play that takes place in late 17th century Salem, Massachusetts, concerning the infamous Witch Trials.

Tucked away in the dialogue are some very striking points concerning the outworkings of religious bondage. Of course, The Crucible is an imaginative literary account of Puritan life in early America, but it does capture and do justice to the religious spirit of that time (cf. Alice Morse, “Sketches of Life in Puritan New England,” Searching Together, 11:4, 1982).

We are picking up at the point in the story when Rev. John Hale has come to visit John and Elizabeth Proctor because Elizabeth’s name had been mentioned in court, insinuating that she might be a witch. Salem pastor Samuel Parris had summoned outsider John Hale to help, based on his alleged expertise regarding witchcraft.

Hale: In the book of record that Mr. Parris keeps, I note that you are rarely in the church on Sabbath Day.

Proctor: No, sir, you are mistaken.

Hale: Twenty-six times in seventeen months, sir, I must call that rare. Will you tell me why you are so absent?

Proctor: Mr. Hale, I never knew that I must account to that man for whether I come to church or stay at home. My wife was sick this winter.

Hale: So I am told. But you, Mister, why could you not come alone?

Proctor: I surely did come when I could, and when I could not, I prayed in this house.

Hale: Mr. Proctor, your house is not a church; your theology must tell you that.

Proctor: It does, sir, it does; and it tells me that a minister may pray to God without him having golden candlesticks upon the altar.

Hale: What golden candlesticks?

Proctor: Since we built the church, there were pewter candlesticks upon the altar; Francis Nurse made them, y’know, and a sweeter hand never touched the metal. But Parris came, and for twenty weeks he preached nothin’ but golden candlesticks until he had them. I labor the earth from dawn of day to blink of night, and I tell you true, when I look to heaven and see my money glaring at his elbows – it hurt my prayer, sir, it hurt my prayer. I think, sometimes, the man dreams cathedrals, not clapboard meetin’ houses.

Hale (thinks, then): And yet, Mister, a Christian on Sabbath day must be in church. (Pause.) Tell me – you have three children?

Proctor: Aye. Boys.

Hale: Why is it that only two are baptized?

Proctor (starts to speak, then stops, then, as unable to restrain this): I like it not that Mr. Parris should lay his hand upon my baby. I see no light of God in that man. I’ll not conceal it.

Hale: I must say it, Mr. Proctor; that it is not for you to decide. The man’s ordained, therefore the light of God is in him.

Proctor (flushed with resentment but trying to smile): What’s your suspicion, Mr. Hale?

Hale: No, no. I have no –

Proctor: I nailed the roof upon the church, I hung the door –

Hale: Oh, did you! That’s a good sign, then.

Proctor: It may be that I have been to quick to bring the man to book, but you cannot think we ever desired the destruction of religion. I think that’s in your mind, is it not?

Hale (not altogether giving way): I – have – there is a softness in your record, sir, a softness.

Elizabeth: I think, maybe, we have been too hard with Mr. Parris. I think so. But for sure we never loved the Devil here.

Hale (nods, deliberating this. Then, with the voice of one administering a secret test): Do you know your Commandments, Elizabeth?

Elizabeth (without hesitation, even eagerly): I surely do. There be no mark of blame upon my life. Mr. Hale, I am a covenanted Christian woman.

Hale: And you, Mister?

Proctor (a trifle unsteadily): I – am sure I do, sir.

Hale (glances at her open face then at John, then): Let you repeat them, if you will.

Proctor: The Commandments.

Hale: Aye.

Proctor (looking off, beginning to sweat): Thou shalt not kill.

Hale: Aye.

Proctor (counting on his fingers): Thou shalt not steal. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s goods, nor make unto thee any graven image. Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord in vain; thou shalt have no others gods before me. (With some hesitation). Thou shalt remember the Sabbath Day and keep it holy. (Pause. Then). Thou shalt honor thy father and mother. Thou shalt not bear false witness. (He is stuck. He counts back on his fingers, knowing one is missing). Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.

Hale: You have said that twice, sir.

Proctor (lost): Aye. (He is flailing for it).

Elizabeth (delicately): Adultery, John.

Proctor (as though a secret arrow had pained his heart): Aye. (Trying to grin it away – to Hale). You see, sir, between the two of us we do know them all. (Hale only looks at Proctor, deep in his attempt to define this man. Proctor grows more uneasy). I think it be a small fault.

Hale: Theology, sir, is a fortress; no crack in a fortress may be accounted small. (He rises; he seems worried now. He paces a little, in deep thought).

Proctor: There be no love for Satan in this house, Mister.

Hale: I pray it, I pray it dearly. (He looks to both of them, an attempt at a smile on his face, but his misgivings are clear).

————————————————————————————————————————

The basic problems religion brings are the same today as they were in 17th century Puritan America. Back then the church leaders had the magistrates backing them. While today’s pastors do not have the extra clout that civil authority brings, they nevertheless wield significant control over many church-goers lives. I would like to highlight how Christ is eclipsed in religious settings like the one depicted in The Crucible.

** “What golden candlesticks?” Many manifestations of Christianity are old covenant-based. Types, shadows, tithes and rules become the focus instead of Christ.

The golden candlestick (lampstand) was part of the old covenant economy (Exodus 25:31-39; 37:17-24; Hebrews 9:2). The purpose of this item was to bring light into the Holy Place. Christ is the reality of what this lampstand symbolized. He is the light in His people, and thus His assemblies emanate His light to one another and to the world.

In The Crucible, John Proctor was upset that the pewter candlesticks were replaced by golden ones, which pastor Parris wanted so badly. People have a tendency to replace the light of Christ with physical objects of devotion, and the like.

In Revelation, golden candlesticks symbolize Christ in the ekklesias. To one assembly Christ announced that if they did not turn from their waywardness, He would remove His presence from them – “I will come to you quickly and remove your lampstand out of its place” (Rev. 2:5).

Religion moves so quickly to tangible objects, things, “its” that are not Christ, even though His name may be attached to them. Jesus is about reality – the reality of His life in people and in His ekklesia.

And so many resources are squandered on that which is not the Lord. Proctor lamented, “I labor the earth from dawn of day to blink of night, and I tell you true, when I look to heaven and see my money glaring at his elbows – it hurt my prayer, sir, it hurt my prayer.” Whenever the wrong things are exalted, Jesus is pushed aside. Layers of religion smother the expression of Christ’s Life.

** “A Christian on Sabbath Day must be in church.” Paul affirmed that the Sabbath was a shadow and that Christ is the fulfillment and reality of it. Jesus said, “Come to Me and I will give you rest [sabbath].” In the new covenant, the only way to “keep the Sabbath” is to cease from your own works and rest in Christ. Jesus is our Sabbath, not a day of the week. Sabbath is about a resurrected person, not a 24-hour period of abstention.

** “Do you know your commandments, Elizabeth?” Most of Christianity still camps around Sinai, not around Golgotha. Most people seem oblivious to the fact that Exodus 20 is rooted in an earthly exodus out of a physical country, Egypt – “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of Egypt.” That event was a pointer to the fact that the future Messiah would accomplish an exodus in Jerusalem, and bring His people out of the land of sin and bondage (Luke 9:31).

There is only one command rooted in Christ’s new exodus – the “new commandment” to love each other as He loved us on the cross (John 13:34-35).

We must recall that life in early Puritan America was carried out in an Old Testament atmosphere (cf. W.B. Selbie, “The Influence of the Old Testament on Puritanism,” Searching Together, 8:3, 1979). Their exit from Britain was cast in Old Testament typology. England was viewed as “Egypt”; the Puritans saw themselves as a “New Israel”; the Atlantic Ocean was seen as the Red Sea; the land ahead became Canaan, flowing with milk and honey; and the native Indians were viewed as the “heathen,” to be cast out of the land. Is it any wonder, then, that the emphasis fell on outward, earthly elements and not the Life and Light of Jesus in His people?

(For further development of the New Exodus, the New Spirit and the New Commandment, see my review of The Ten Commandments Twice Removed, http://www.exadventist.com/Home/Articles/ReviewofTCTR/tabid/497/Default.aspx)

** Proctor: “I see no light of God in that man” . . . . Hale: “The man’s ordained, therefore the light of God is in him.” Hale’s reply gets to the heart of a huge problem. Instead of a person’s influence being connected to the Life of Christ flowing through him/her, it is rooted in a religious rite that confers, and apparently assures, the presence of God. This rite is “ordination.” The ordained (clergy) can perform many things that the common person (the laity) cannot.

And one of the most extensive perks “ordained clergy” have control. Tragically, most religion ends up being about power, control and manipulation – making sure the flock stays in line, conforms to the rules, and only colors within the given boundaries (cf. Horace Kallen, “Buildings, The Clergy & Money,” http://www.radicalresurgence.com/page/2/).

In order to ensure conformity, such things as fear, guilt, intimidation, threat of excommunication, no access to the “sacraments,” and loss of the “benefit of clergy” are used to keep the troops in rank.

(For further reflection on “ordination,” cf. Marjorie Warkentin, Ordination: A Biblical-Historical View, Eerdmans, 1982).

** “In the book of record that Mr. Parris keeps, I note that you are rarely in the church on Sabbath Day.” Here is the outworking of religious power. Who comes to the meeting-house, how much they give, and many other such things, are kept track of by those in religious authority. In this way, the “softness of record” can be held over the heads of the faithful when necessary. The “laity” must be in the building every Sunday, but the “clergy” can have golden candlesticks with no accountability.

** “Your house is not a church; your theology must tell you that.” Just as Judaism emphasized its Temple, most other religions are known for their religious structures.

But Jesus builds people, not physical buildings. A striking feature of the early church was that they had no special buildings. They met together around Christ and broke bread in homes. “To the ekklesia at your home” (Philemon 2); “greet the ekklesia in their home” (Rom. 16:5); “with the ekklesia in their home” (1 Cor. 16:19); “salute Nymphas and the ekklesia that meets in her home” (Col. 4:15).

When Constantine sanctioned the Christian religion around AD 325, state money was used to erect its buildings, and pagan places of worship were turned over to the Christians. Since then inordinate attention has been given to buildings with Christ’s name associated with them.

One summary of life in the Middle Ages notes: “In many ways village life centered on the church building. [It was] the largest building in the village” (The Middle Ages: The Church, Madison, WI: Knowledge Unlimited, 2002).

The church certainly does not have the clout it had back then. And, too, in the Middle Ages there was only one church building – a Roman Catholic one. Now there can be many church buildings – in America, darn close to one every half-mile! (Cf. my A Church Building Every ½ Mile: What Makes American Christianity Tick?)

** “Theology, sir, is a fortress; no crack in a fortress may be accounted small.” Ah, here is the seed-thought for 25,000 denominations. Each group thinks their “theology” is the closest to the truth, and hence cracks cannot be tolerated. That’s our problem. We are trying to construct a theology – create an impenetrable fortress.

Since Mr. Proctor could not recall one of the ten commandments, Rev. Hale felt like he had some reason to believe that the evil one could have a foothold in their home. In this kind of religion people are judged by how much of the “right” doctrine they know, not if fruit is coming from a branch in union with Christ the Vine.

Because Mr. Proctor did not come to the building as much as Hale and Parris thought he should, and because he could not rattle off “the commandments,” his spirituality was called into question. This is not Christ; this is outward, superficial religion which keeps people in bondage.

If we are brutally honest with church history, it would seem that for the most part activity in the visible church has been about Christ, about believing the right things, about conforming to required patterns of behavior, and about control by church leaders. It has simply not been about the Living Christ expressing Himself through the whole body. It has not been about rivers of living water pouring out of His people, but about keeping the religious machinery well-oiled. As I observed in 1980:

Marriage to Christ brings with it a new relationship; and in this relationship we are to derive our comfort, our duty, our everything from Christ – our Husband, our Bread of Life, our Vine, our Prophet. If we focus on anyone or anything other than Christ, we run the risk of missing everything important (“’As I Have Loved You’: The Starting Point of Christian Obedience,” Searching Together, 9:2, 1980, p.16).

[If you are interested in the actual history in 1692 Salem compared to Miller’s play, here is an article by academic historian Margo Burns: “Arthur Miller’s The Crucible: Fact & Fiction,” http://www.17thc.us/docs/fact-fiction.shtml

The dialogue from The Crucible is from A. Purves/C. Olson/C. Cortes, eds., Literature & Integrated Studies: American Literature, Scott-Foresman, 1997, pp. 95-96. Several words were changed for communication purposes.]

Jon Zens

Author, speaker, editor of Searching Together, itinerant encourager of relational communities.

Author, speaker, editor of Searching Together, itinerant encourager of relational communities.

Appreciated your analysis. It amazes me how many still hold to the Old Covenant or just make a jumble of everything. Thanks again

Old covenant orientation is a persistent problem, isn’t it?

Thanks for the great post, Jon. I read The Crucible in high school, but I had no sight of Christ at the time. Now, I can see where Christ ought to be in the play. Christ is our Fortress, not theology. Christ is the Reality of all the Old Testament shadows. Christ is God’s provision for our every need!

The tragedy that strikes me as I read The Crucible is how in the religious atmosphere the focus shifts to policing people, instead of relishing, adoring and exalting the Lord Jesus.

Yup, I have experienced this “policing”. Early in my walk in Christ, I was kicked out of a church. It broke my heart. I was just exploring my faith and learning what I had in Christ, but my evolving beliefs didn’t fit with the pastor’s beliefs. Fortunately, I had another group of saints to enjoy Christ with. Looking back, I can see God working to bring me out of that and to where He wanted me. Without that pastor’s actions, I don’t know if I would have the same enjoyment of Christ with the saints that I have today.

“in the religious atmosphere the focus shifts to policing people…”

That is why there is so much emphasis on “membership”, “spiritual authority”, and of course, “church discipline.”